Reminder: "Be on time!". Now it needs not to be what it seems! [P1]

People might pay not enough attention to the abstract meaning of time

👋 Hey, Nam here! Long time no see. I attempt to write once in a while for the site to be a self-note as I learn and share lots of unorthodox but unintuitively sane insights about life, humor, business, and philosophy. So in case you want to learn and share your dull but lasting ideas, please subscribe.

Today's post is inspired by Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman.

I want to start by asking this question: Do you ever wish to live without feeling any pressure and stretch to save “time”? Nor would you have to feel guilty of wasting it: let’s take an example of an afternoon break for coffee or walking from working nonstop on an office table, that wouldn’t lead to feeling of you were to shrink “work time”?

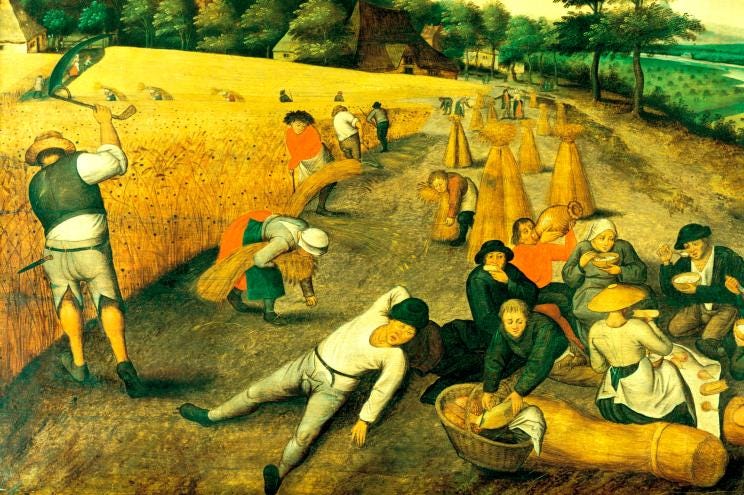

Not long ago, medieval humans didn’t have at all NO such a thing. It isn’t because they were so relaxed, way more than people nowadays, or they were relieved of their fate. It is just simply because they did not have a concrete and sober feeling of time - as a thing - at all which means that they didn’t have any such experience named “time””

Does that sound unorthodoxly strange? Well if that’s the case, let’s assume for now that that way of thinking (about time) is so deeply entrenched on us (so called modern humans) such that we forgot it even is just a *choice* of thinking.

Oliver said:

we’re like the proverbial fish who have no idea what water is, because it surrounds them completely. Get a little mental distance on it, though, and our perspective starts to look rather peculiar.

And that has been so often acknowledged that we think of time as something totally independent and separate from us and the world around us too—"an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences"—in the words of the American cultural critic Lewis Mumford.

Now let me tell a story of time invention since the age of medieval monks, They needed a reliable mechanism to ensure that the entire monastery got up at the appropriate time and who had to start their morning prayers while it was still dark. Therefore, standardizing and making time visible in this way necessarily leads to people thinking of it as an abstract concept with its own existence, separate from the particular activities on which one may spend it. "Time" is what ticks away as the hands travel around the clockface. The steam engine's development is undoubtedly credited with sparking the Industrial Revolution, but one other development was equally important: the clock. By the late 1700s, rural peasants were streaming into English cities, taking jobs in mills and factories, each of which required the coordination of hundreds of people working fixed hours six days a week to keep the machine running.

When considering time in the abstract, it makes sense to begin treating it like a resource that can be traded, sold, and utilized as effectively as possible, much like coal, iron, or any other raw commodity. Prior to this, workers were paid on a piecework basis, receiving a lump sum per bale of hay or per slain pig, or for an ill-defined day's work. The practice of being paid by the hour, however, spread throughout time, and a factory owner who made the most of his workers' hours by extracting as much effort as possible from each worker stood to earn more than one who didn't.

Okay, this post lasts for quite a while. So I decide now to divide this idea of mine about “working for the work’s sake, not time” itself into several more posts.

And if you find these types of posts engaging or have any other comments, please let me know below.

Be sure to subscribe and leave some thoughts! Thank you so much and see you soon 🧡 To be continued…